Close

In the late 17th century, it was in no way certain that the Protestant elite in Ireland would hold power in the Catholic-majority country for centuries to come. The Protestants who had displaced the Catholic landowners while Cromwell, a militant Protestant, reigned over Great Britain felt their vulnerability with every chance encounter with a resentful Catholic peasant. In the 1649 Irish Rebellion, they had seen the Irish rise up and murder their Protestant landowners, unleashing an avalanche of violence on the Protestant families who had stolen their land and repressed their faith.

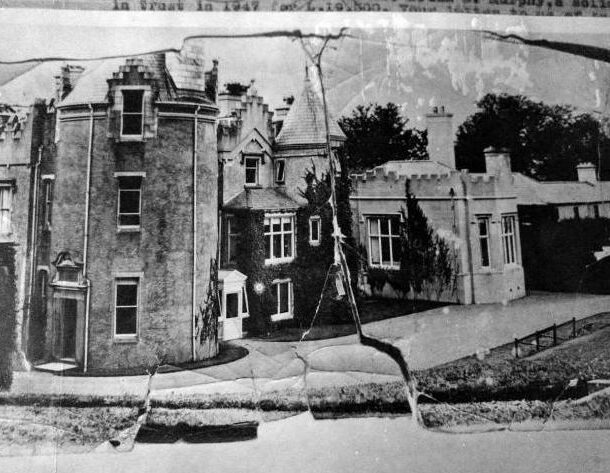

Thomas Bellingham was one of these Protestants. His father had served as a cavalry officer under Cromwell in the Conquest of Ireland between 1649 and 1653. Cromwell awarded him with an estate in County Louth as part of the mass dispossession of Irish Catholic landowners. There, Bellingham built a castle to put his family’s hold on Irish soil in stone. His son, Thomas, inherited Bellingham Castle. Decades passed, but stability remained elusive in Ireland. The Catholic-leaning Stuart kings returned to the throne after Cromwell died, threatening the status of Bellingham and every other Protestant family installed in a position of wealth and power by Cromwell. But then the tide shifted yet again when William and Mary, the king’s Protestant daughter and her Dutch husband, arrived in England and deposed the unpopular King James. In Ireland, Jacobites—or supporters of King James—rallied around the fallen king, determined to resist the return of staunch Protestants to the throne. Catholic Jacobites attacked the Protestant elite. They burned Bellingham Castle, itself a symbol of Protestant usurpers, and threatened to kill any Protestant noble they could track down. Bellingham escaped to England.

The deposed King James fled to Ireland where he led a motley army of Catholic peasants and dispossessed Catholic nobles in a desperate bid to regain the throne. For the Irish, the Jacobite Uprising had less to do with European affairs or the throne of England than the ethnic and religious strife within their country. Catholics, the overwhelming majority, saw their rights to hold public office, practice their religion, and own land vanish as a small number of Protestant families consolidated their grip on power and Irish resources. King James was their last hope. But William, the new king, was determined to secure the English throne. He followed King James to Ireland with an army of 36,000 men, many of them seasoned fighters from Denmark and the Netherlands equipped with flintlock muskets. Bellingham joined the new king’s army, offering his knowledge of the terrain of northern Ireland to strategists at crucial moments of the campaign. The Jacobite army only had 26,000 men. The Catholic nobility were skilled cavalrymen, but they were out-numbered and out-gunned. Many of the peasant rank and file were armed with nothing but scythes, and the few muskets they had were cumbersome and out-of-date. At the Battle of Boyne, not far from Bellingham Castle, the two armies clashed at a fjord in the River Boyne. Bellingham knew the land—how the morning mist would shield the army from the enemy, how the river bent and flowed, and where the opposing army may approach. He enabled the Protestant army to outmaneuver the Jacobites. The Catholic cavalry rushed at William’s army, unphased by the barrage of bullets. But wave after wave of William’s professional soldiers overwhelmed them, forcing them to retreat. The Jacobites never regained the upper hand. Soon, King James fled to France and his army dispersed.

The Battle of Boyne marked the last moment when the Catholic majority mounted a significant challenge to the Protestant Ascendancy that defined Irish political and social life for the next two centuries. Bellingham rebuilt his family’s castle, reaffirming his claim to Irish land. Protestants built monuments to the battle and King William across northern Ireland. On the anniversary of the Battle of Boyne, they even acted out key moments in the battle. And when the Irish War of Independence broke out in 1916, Catholics still had bitter memories of their defeat that had been passed down over generations. They tore down the monuments, determined to decapitate the stony symbols of English repression.